Designing my medieval fyddle

Posted on 2023-11-023378 words

I have spent the last few months (sporadically) looking into the fyddle, how it looked, how it was tuned, and of course what makes a fyddle a fyddle. Since I plan on getting started on actual construction soonish, I thought this would be a good opportunity to go over my findings.

Methodology

There are, unfortunately, very few surviving extant fyddles. I have seen some extant viols from around the 17th century (if I recall correctly), but these are of little use to me. While the viol is a beautiful instrument and I would very much like to learn how to play one, it is a much younger instrument than the fyddle. As it is from the reneissance, it is constructed like a modern violin, using bent separate ribs, back and belly. As mentioned in the last post, early medieval fyddles had their ribs, back and neck be carved from a single piece of wood. Since this is what I’m aiming for, using viols for reference makes little sense.

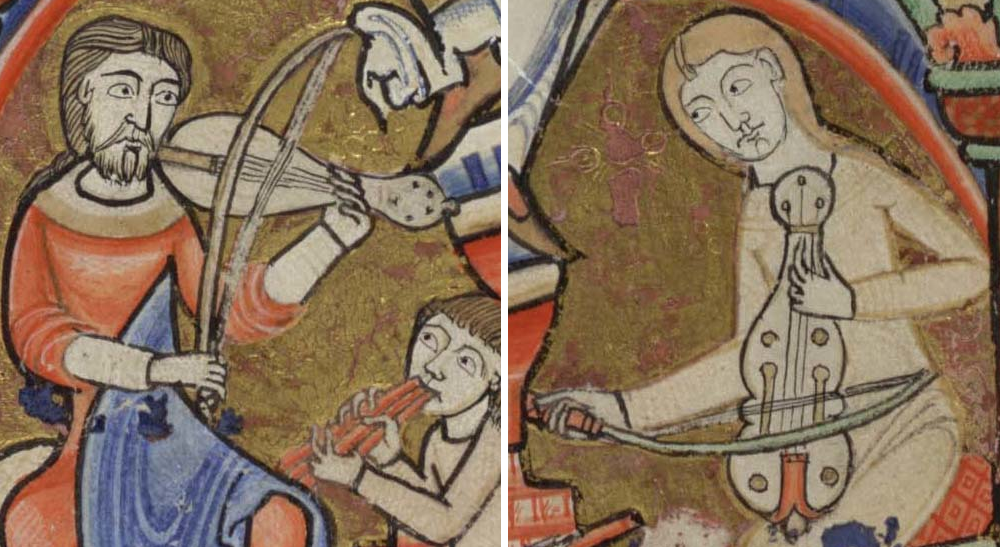

No, instead I’ve had to "“resort”" to studying extant manuscripts and paintings, and use those as reference. Fyddles were quite popular instruments for large parts of medieval europe, so there is no lack of depictions.

These depictions, along with some guestimations, some borrowing from the work of real luthiers, and articles (academic or otherwise) on the topic have been what I’ve based my design on.

What even is a fyddle?

Before we dive into the quite messy design of a fyddle, we should define what a fyddle actually is, and what it isn’t. This may seem a bit unnecessary at first, but once we get into the shape of this thing it’ll become apparent that it’s not obvious. The shapes of medieval fyddles seems to have been about as diverse as the shapes of modern electric guitars (well, almost), and it shares its shape with another instrument that was also very popular in medieval Europe - the rebec.

Before we get into distinguishing the fyddle from the rebec, let’s go over what a fyddle is. The fyddle is stringed instrument played with a bow that is roughly violin-shaped. It seems that the number of strings varied between three and six, but that four or five seems to have been the norm (Page, 1979). At least for the five-stringed fyddles, it seems to have been farily common that one is “floating” off the fingerboard, so that it can only be played open. As such, it would’ve either been played as a drone string, or plucked with the thumb. The back and belly are flat, and it seems that the bridge was also commonly flat. As the strings were attached to a separate string holder, the bridge would apply downward preassure on the soundboard. Finally (for now, I’ll go over everything in more detail further down), the fingerboard could be fretted with gutstring, but it wasn’t always.

Now that we have some idea of what a fyddle is, let’s make sure we also know what it isn’t. This is important due to the existence of the rebec. Like I said before, the shape of the fyddle varied quite a lot, and one of the more common shapes seems to have been that of a pear (called “piriform”). Unfortunately, rebecs are also piriform instruments. They also have three to five strings that are played with a bow, they’re of roughly the same size, and they’re held the same when played.

So then, what even distinguishes the two? Could it be that they’re just two words for the same instrument? Unfortunately, it’s not that easy, but there are quite clear differences. They’re just not always clear in depictions. There are three main differences, two of which can be seen (Pittaway, 2015):

- The rebec has a bowl-shaped back, while the fyddle’s back is flat. Unfortunately, not always obvious in extant deptictions.

- The rebec had a narrow, crescent-shaped pegbox, while the pegbox of a fyddle is flat and wide.

- Finally, the rebec is tuned in fifths (like a violin), while the tuning of a fyddle is varied (surprising, right?) and not uniform.

So, now that we know roughly what a fyddle is, and what it isn’t, let’s get into the meat of my research into the design.

Shape

Yes, the shape. As mentioned, there were no rules. Like, literally no rules. Looking at depictions in manuscripts and art, shapes seem to vary a lot. There are examples of oblongish fyddles, there are fyddles shaped more like a “soft violin”. The extant fyddle from the Mary Rose is rectangular with “chamfered” corners. There are some truly nutty shapes, like one example from the Hunterian Psalter where there’s a “bump” in the middle of the waist. And, of course, there is the piriform fyddles that look a lot like rebecs. For the purposes of this project (and my mental health), I’ve chosen to only consider piriform instruments with an obviously bowl-shaped back or a crescent-shaped pegbox to be a rebec, as per the discussion above. If neither feature is present or obvious, I’ve considered it to be a fyddle. Would this stand up to scrutiny in a peer-reviewed journal? Probably not, but I’m not writing one of those, so I don’t care.

Examples of some of these shapes, funky and reasonable alike, can be seen below.

The figures above is quite a small sample, but they still do show that a variety of shapes have been used all the way back to the 12th century.

Strings

Like mentioned when discussing what a fyddle is and isn’t, the number of strings used seems to have varied quite a bit as well. There are depictions of the instrument from three up to six strings, in different configuration. One such configuration that sticks out is the five-string fyddle where one string is offset from the fingerboard, by having it “connect” with the pegbox on the side rather than from the top. This means that the string can only be played open, turning it into a drone or bourdon. From extant depictions of such fyddles, it seems that this string may also have been plucked with the thumb. Examples of this can be seen in the figure below.

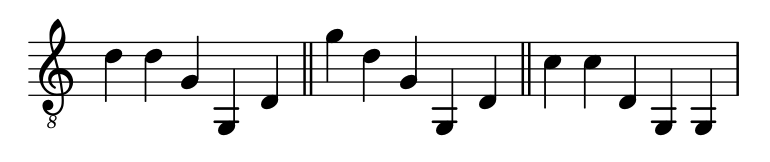

While the number of strings seems to have been up to personal prefernce of the fyddler, or perhaps the luthier who built it, there seems to have bee quite strong opinions on the matter. Hieronymus de Moravia (or Jerome of Moravia) writes in his treatise Tractus de Musica that a fyddle “has, and must have” five strings (Page, 1979). He also provides three tunings for fyddles with five strings, which can be seen below.

It is interesting to note, here, that these tunings are a whole octave below that of a modern violin. When setting out on this project I was under the impression that the fyddle was tuned the same as a violin. This misconception probably comes from the fact that there are modern reconstructions that are tuned in fifths, like a violin, and that the rebec was historically tuned this way as well.

Bridge

Highly related to the amount of strings and their configuration is, of course, the bridge. As with a violin, the bridge is held in place by the downward tension created between the nut and the stringholder. As with everything else on this instrument, the bridge has been depicted in a number of ways - flat, curved, castellated, etc. It seems to be a common denominator that the height of the bridge was less than or equal to it’s width, which is not necessarily the case with the modern violin. This makes for low action, i.e. the space between the fingerboard and the strings is quite small. This can be seen below.

As for each kind of bridge will affect the tone, I do not know. I’ve never experimented with making a violin bridge, so this may be something worth experimenting with.

Stringholder

The stingholder is quite uninteresting in the context. As with the modern violin, it is quite simply a piece of wood to which the strings are attached. The stringholder is quite simple in its construction, but from deptictions it seems that it may have been intricately decorated.

Fingerboard

As with the stringholder, the fingerboard is quite simplistic, if it is at all present in extant depictions. One thing to note with the fingerboard is that its shape would necessarily be informed by the bridge - a flat bridge with a concave fingerboard would mean that the action of the outer strings is higher than that of the middle strings, and vice versa for a flat fingerboard with a curved bridge. This doesn’t make it impossible to play the instrument, of course, but it would affect intonation and probably make it feel a bit awkward to play. In essence this means that I’ll need to decide at least if I want a flat or curved bridge before starting work on the fingerboard.

Pegbox

Coming around to the pegbox, more variety starts showing back up in the depictions. There are some general trends, though. Diamond or spade shaped pegboxes show up frequently, as do round ones. Other shapes do occur though.

Another thing that’s quite interesting is the configuration of the tuning pegs. Firstly, there is the question of whether the stings attach above or below the pegbox. Depictions show both fyddles where the strings attach above the pegbox, and versions where there are holes drilled just above the nut to enable strings to pass through the material and be wound around the pegs on the underside of the pegbox, as shown below.

There is also the question of where the fifth string go (if one exists). If it is not offset from the fingerboard it will obviously attach to the tuning pegs the same way as the other strings, but if it is offset there are alternatives here as well. Some depictions show that there is a hole in the side of the pegbox that the bourdon is passed through. Other depictions show that the fifth tuning peg simply sticks out to the side of the pegbox, as depicted in Cappellone degli Spagnoli above, achieving the same effect.

Soundholes

Yea, there are no rules, go nuts. Round holes, C-holes, D-holes, rosetted squares, there’s examples of it all. Except the modern f-holes, which first appeared in the renaissance (Nia et al., 2015). The figures earlier in the post show quite the variety of soundhole shapes, so I’ll spare you the repeat figures.

Size

The final thing to go over before moving into my own design decisions is the size. This is a tricky one, since there are only two extant fyddles that have “survived” to this day. Depictions are great for determining certain things, but determining the size is quite hard from artwork. I suspect, however, that it is with the size of the intstrument as with everything else: it varied, and probably quite a lot. The sizes I’m interested in the most is the volume of the soundbox and the scale length (i.e., the length of the vibrating part of the string, from bridge to nut), as these parameters will affect the instrument the most.

There are some different approaches to take here - look at extant depictions of the fyddle, figure out its size relative to the one playing it, and then figuring out the size by assuming an average sized human. This could be tricky though, since depiction may not be in favourable angles to allow these estimations to be done easily, and since the depictions of the size of the fyddle or player may not be accurate.

Instead, I’m going to slightly cheat and use measurements from modern reconstructions. Early Music Shop sells three where the sizes are defined, and using this in combination with taking measurements on my own violin and viola should give me a reasonable idea of what may be suitable. The mesaurements are as follows (all measurements in millimeters):

| Measurement | Fyddle 1 | Fyddle 2 | Fyddle 3 | Violin | Viola |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale length | 298 | 360 | 358 | 325 | 351 |

| Total length | 605 | 640 | 640 | 600 | 654 |

| Max width | 207 | 218 | 205 | 205 | 225 |

| Max height | 70 | 128 | 90 | 82 | 93 |

| Nut width | 30 | 38 | 30 | 25 | 28 |

| Fingerboard length | 218 | 216 | 225 | 270 | 286 |

It should be noted that the first fyddle, as well as the violin and viola, are all four-stringed. The other two fyddles are both five-stringed with an offset bourdon. This is something to consider when looking at the nut width. The first fyddle is also tuned in fifths, like a violin.

What we can see from the table is that the scale length of the first fyddle is more similar to that of my violin than the other two fyddles, which are closer to my viola. The scale length of the first fyddle is, however, still almost 30mm shorter than that of my violin.

In general, it seems that most measurements of the second and third fyddles, which are a bit larger than the first, are closest to the measurements of my viola. The two exceptions to this are the lengths of the fingerboards as well as the maximum width. The width seems to more closely match my violin for most fyddles.

Interestingly, all fyddles have a significantly shorter fingerboard than both my violin and viola, leading me to believe that the neck is also shorter in proportion to the body of the instrument. The fyddles from Early Music Shop doesn’t have the length of the neck specified, so I did some pixel measurements of the front-facing pictures of the instruments. While this is not the most accurate, it am mostly interested to see if the neck is indeed shorter relative to the rest of the body on the fyddles.

| Measurement | Fyddle 1 | Fyddle 2 | Fyddle 3 | Violin | Viola |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total length | 1699px | 1766px | 1790px | 600mm | 654mm |

| Neck length | 440px | 286px | 311px | 130mm | 139mm |

| Neck proportion | 26% | 16% | 17% | 22% | 21% |

Looking at the table above1, we see that the first fyddle actually has a longer neck than both my violin and viola, interestingly. Glancing at my modern instruments, I think this is likely because the string holder is very long on the fyddle, reaching almost half way up the body. The two larger fyddles, however, have significantly shorter necks, as expected.

While I was at it with the pixel measurements, I took the opportunity to measure the waist of the instruments as well, results below:

| Measurement | Fyddle 1 | Fyddle 2 | Fyddle 3 | Violin | Viola |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | 590px / 207mm | 656px / 218mm | 607px / 205mm | 205mm | 225mm |

| Middle | 505px / 177mm | 613px / 204mm | 524px / 177mm | 160mm | 182mm |

| Minimum | 483px / 169mm | 563px / 187mm | 500px / 169mm | 104mm | 123mm |

As expected, the waist of the fyddles is significantly wider than that of the modern instruments. What surprises me is that fyddles one and three have the same measurements of the body width. From just looking at them, I would not have expected this, I would’ve thought that the first fyddle has bigger differences between it’s measurements. This is probably due to the fact that since the neck of the first fyddle is 25% of the length, the body is shorter and therefore wider in proportion to its length.

My own fyddle

Now, with all the measuring, reading and manuscirpt-diving out of the way, it’s time to start thinking about the instrument I’m going to build. We know know what a fyddle could look like, how many strings it could have, how the bridge could be shaped. Lots of “could”, not very much “will”. So let’s change that.

I have to actually make some decisions if I am to have a finished insturment by May AS59, so here goes. My very own fyddle will feature:

- A waised body (i.e., the shape of the reference fyddles from Early Music Shop)

- Five strings, with one being offset from the fingerboard

- A flat bridge, probably?

- A spade-shaped pegbox, with strings attaching to pegs on the underside and the “bourdon peg” sticking out from the side

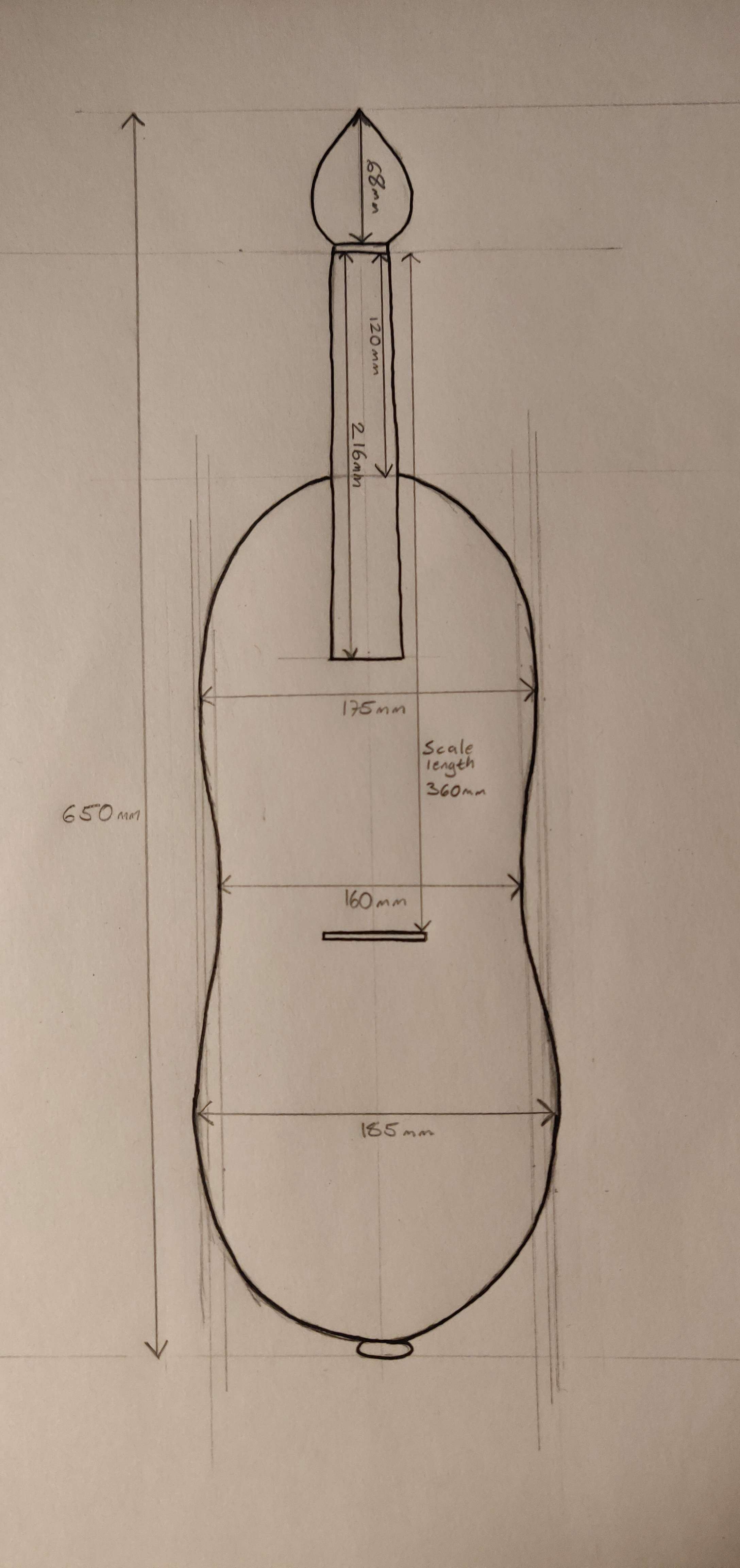

- 650mm long, with a scale length of 360mm, and a max width of 185mm. Full plans with measurements below

Regarding the size, my intuition tells me that a larger instrument would be more suitable for the lower ranges, since a violin is smaller than a viola, and a viola is smaller than a cello. However, I don’t have enough theoretical background in instrument construction to make any firm statements. There is also another factor to consider here, which is that I don’t have an infinite supply of wood. I have a block of basswood that I’m going to use for this project, so size is limited by its dimensions.

Looking at the plans, I find that I don’t quite like the shape - the body is a bit too long and narrow. When making the actual paper template I’ll use to transfer the design to my wood, I’ll play around a bit with the proportions to see if I can find a shape that I find more pleasing.

Other design elements, like decorations and shape of the soundholes will be left for later, I don’t need to decide that until I start working on those components respectively.

One thing to consider is the possibility of making replaceable bridges, so I can try out different versions to see what I like. As discussed earlier, the shape of the bridge should reasonably affect the shape of the fingerboard, which means I’ll have to have one bridge shape in mind when making it. But it should be possible to play around with, even if playing may become a bit awkward with “the wrong” bridge. Changing the bridge should be a fairly easy thing to do as well, since the soundpost is a renaissance invention. Earlier instruments had braced lids, much like the guitars of today. This means that even if you remove all downward tension on the lid, you don’t risk the soundpost falling.

Anyway, this post is now absolutely humongous. The fyddle really is a very diverse and interesting instrument, and I really look forward to getting stared with shaping it. But for now, enough rambling.

References

Nia, H. T., Jain, A. D., Liu, Y., Alam, M.-R., Barnas, R., & Makris, N. C. (2015). The evolution of air resonance power efficiency in the violin and its ancestors. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 471(2175). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2014.0905

Page, C. (1979). Jerome of moravia on the rubeba and viella. The Galpin Society Journal, 32, 77–98. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/841538

Pittaway, I. (2015). The rebec: A short history from court to street. https://earlymusicmuse.com/rebec/.

Since I cannot get exact measurements for the fyddles here, all proportions are rounded to the closest integer.↩︎